Herb Pennock

| Herb Pennock | |

|---|---|

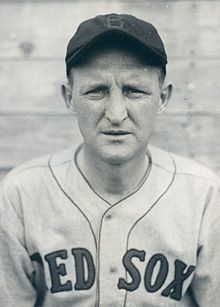

Pennock in 1934 | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: February 10, 1894 Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| Died: January 30, 1948 (aged 53) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. | |

Batted: Switch Threw: Left | |

| MLB debut | |

| May 14, 1912, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 27, 1934, for the Boston Red Sox | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 241–162 |

| Earned run average | 3.60 |

| Strikeouts | 1,227 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1948 |

| Vote | 77.7% (eighth ballot) |

Herbert Jefferis Pennock (February 10, 1894 – January 30, 1948) was an American professional baseball pitcher and front-office executive. He played in Major League Baseball from 1912 through 1933, and is best known for his time spent with the star-studded New York Yankee teams of the mid to late 1920s and early 1930s.

Pennock was signed by the Philadelphia Athletics in 1912, but was used sparingly by the Athletics and the Boston Red Sox, who bought his contract in 1915. After returning from military service in 1919, Pennock became a regular contributor for the Red Sox. The Yankees acquired Pennock after the 1922 season, and he served as a key member of the pitching staff as the Yankees won four World Series championships. After retiring as a player, Pennock served as a coach and farm system director for the Red Sox, and as general manager of the Philadelphia Phillies.

Pennock was regarded as one of the greatest left-handed pitchers in baseball history. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1948, and was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame later that year.

Early life

[edit]Pennock was born on February 10, 1894, in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. His father, Theodore Pennock, and mother, Mary Louise Pennock (née Sharp), were of Scotch-Irish and Quaker descent.[1] His ancestors came to the United States with William Penn.[2] Herb was the youngest of four children.[1]

Pennock attended Westtown School and Cedarcroft Boarding School, where he played for the baseball team. After struggling as a first baseman, with weak offense and a inability to throw the ball straight, Pennock was converted by his Cedarcroft coach into a pitcher.[1]

Professional baseball career

[edit]Philadelphia Athletics

[edit]While pitching at Cedarcroft, Pennock threw a no-hitter to catcher Earle Mack, the son of Connie Mack, manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, in 1910. Pennock agreed to sign with the Athletics at a later date.[3] Mack signed Pennock in 1912 to play for his collegiate team based in Atlantic City. Pennock's father insisted that he sign under an alias in order to protect his collegiate eligibility. Pennock threw a no-hitter against a traveling Negro league baseball team, and Mack promoted him to the Athletics.[1] Mack intended for Pennock to be one of the prospects who would replace star pitchers Eddie Plank, Chief Bender, and Jack Coombs.[4]

Pennock made his major league debut with the Athletics during their 1912 season on May 14, allowing one hit in four innings pitched.[1] He was the youngest person to play in the American League (AL) that season.[5] Former major leaguer Mike Grady, a neighbor of Pennock's in Kennett Square, took Pennock under his wing, while Bender taught Pennock to throw a screwball.[1]

Pennock missed most of the 1913 season with an illness, but was able to rejoin the team late in the season.[1][6] In the 1914 season, Pennock posted an 11–4 win–loss record with a 2.79 earned run average (ERA) in 151+2⁄3 innings pitched for the Athletics, and pitched three scoreless innings in the 1914 World Series, which the Athletics lost to the Boston Braves. Mack let Bender go after the season, naming Pennock his Opening Day starting pitcher in 1915. On Opening Day, Pennock threw a one-hit complete game shutout against the Boston Red Sox.[1] However, as the Athletics struggled, Pennock's nonchalant playing style drew Mack's ire. Concluding that Pennock "lacked ambition", Mack sold Pennock to the Red Sox for the waiver price of $2,500 ($75,296 in current dollar terms).[1][7] Mack later regarded this sale as his greatest mistake.[8]

Boston Red Sox

[edit]With a deep pitching staff in place, the Red Sox loaned Pennock to the Providence Grays of the International League in August for the remainder of the 1915 season.[1][9] He split the 1916 season between the Red Sox and the Buffalo Bisons, also in the International League. With Buffalo, Pennock pitched to a 1.67 ERA, as Buffalo won the league pennant.[10] Though the Red Sox won the 1915 and 1916 World Series, Pennock did not appear in either series.[11][12]

Pitching in minor league baseball, Pennock began to regain confidence.[1] However, Boston manager Jack Barry used Pennock sparingly in the 1917 season, and Pennock enlisted in the United States Navy in 1918.[13] Pennock pitched for a team fielded by the Navy, defeating a team composed of members of the United States Army in an exhibition for George V, the King of England in Stamford Bridge stadium. After the game, Ed Barrow, the new manager of the Red Sox, signed Pennock to a new contract after promising to use him regularly during the 1919 season.[1]

Pennock received only one start apiece in the months of April and May, as the 1919 Red Sox relied on George Dumont, Bill James, and Bullet Joe Bush, leading Pennock to threaten to quit in late-May unless Barrow fulfilled his earlier promise to Pennock. Barrow continued to use Pennock regularly after Memorial Day,[1] and Pennock finished the season with a 16–8 win–loss record and a 2.71 ERA in 219 innings pitched. He served as the team's ace pitcher in the 1920 season, but subsequently settled in as the Red Sox' third starter.[1] After the 1922 Red Sox campaign, in which he went 10–17, and had seven wild pitches, leading the AL,[14] the New York Yankees began to negotiate with the Red Sox to acquire Pennock.[15] The Yankees traded Norm McMillan, George Murray, and Camp Skinner to the Red Sox for Pennock that offseason.[16]

New York Yankees

[edit]Pennock pitched to a 19–6 win–loss record in the 1923 season, his first with the Yankees, leading the American League (AL) in winning percentage (.760) and finishing sixth in wins.[17] Pitching in the 1923 World Series, Pennock defeated the New York Giants in game two, on October 11, to end their eight-game World Series winning streak.[1][18] He recorded a save in securing the Yankees' win in game four, and pitched to the win in game six on one day of rest, clinching the Yankees' first World Series championship.[1][18] Umpire Billy Evans called it "the greatest pitching performance I have ever seen", as Pennock "had nothing."[1][19]

In the 1924 season, he pitched to a 21–9 win–loss record with a 2.83 ERA while striking out a career-high 101 batters. His win total was second in the AL, behind Walter Johnson, while his ERA was third behind Johnson and Tom Zachary, and he finished fourth in strikeouts behind Johnson, Howard Ehmke, and teammate Bob Shawkey.[20] Pennock's 277 innings pitched and 1.220 walks plus hits per inning pitched (WHIP) ratio led the AL in the 1925 season, while his 2.96 ERA was second-best, behind Stan Coveleski.[21] In the 1926 season, he posted a career-high 23 wins, finishing second in the AL to George Uhle. He again led the AL in WHIP (1.265), and issued the fewest walks per nine innings pitched (1.453).[22] During the pennant race, The Sporting News called Pennock the "best left-hander in the majors".[1] Pennock earned the wins in game one and game five of the 1926 World Series. He finished game seven of the series, which the Yankees lost to the St. Louis Cardinals.[23]

The Yankees reached the World Series, facing the Pittsburgh Pirates. Pennock pitched a complete game against the Pirates in game three of the 1927 World Series, not allowing a hit until the eighth inning. Pennock's performance drew praise from teammate Babe Ruth.[24] The Yankees swept the series from Pittsburgh.[25] After pitching a three-hit shutout against the Red Sox on August 12, 1928, he missed the remainder of the season, including the 1928 World Series, with an arm injury. His five shutouts and 0.085 home runs per nine innings pitched led the AL. His 2.56 ERA trailed only Garland Braxton, while his 17 wins tied for eighth place.[26] Though the Yankees defeated the Cardinals in the 1928 World Series,[27] the Yankees' starting rotation without Pennock was likened to "a three-stringed ukulele."[1]

In the 1929 season, Pennock saw his pitching time and pitching quality diminish. Over the rest of his career, he never posted more than 189 innings pitched in a season and his ERA rose to over 4.00. He suffered from bouts of neuritis in 1929 and 1930.[28] Pennock won his 200th career game during the 1929 season, becoming the third left-handed pitcher to reach that mark.[1] He led the AL in walks per nine innings pitched in 1930 (1.151)[29] and 1931 (1.426).[30] Pennock pitched four innings of relief against the Chicago Cubs in the 1932 World Series, recording two saves.[31] The New York chapter of the Baseball Writers' Association of America named him their player of the year.[32]

In 1933, serving exclusively as a relief pitcher, Pennock had a 7–4 win–loss record in 23 appearances.[33] After the 1933 season, the Yankees honored Pennock with a testimonial dinner on January 6, 1934, and then gave him his release.[1][32]

Return to Boston

[edit]Eddie Collins, a former teammate with the Athletics now serving as the general manager of the Red Sox, signed Pennock to their 1934 roster.[33] In his last season pitching in the major leagues, Pennock served as a relief pitcher for the Red Sox.[1]

Pennock retired with a career record of 241 wins, 162 losses, and a 3.60 ERA. Pennock pitched in five World Series, one with Philadelphia and four with New York. He was a member of four World Series championship teams. In World Series play, Pennock amassed a 5–0 career win–loss record with three saves, becoming the second pitcher to win five World Series games, after Coombs.[34] Pennock was a part of seven World Series championship teams (1913, 1915, 1916, 1923, 1927, 1928, and 1932), though he played in four World Series as a member of the winning team. Many, including Mack, considered Pennock among the greatest left-handed pitchers of all time.[1][8]

Post-playing career

[edit]Pennock became the general manager of the Charlotte Hornets, a Red Sox' farm team of the Piedmont League, prior to the 1935 season.[35] He returned to the Red Sox in 1936 as the first base and pitching coach under manager Joe Cronin.[36] He served in this role through the 1938 season. In 1939, Pennock became the assistant supervisor of Boston's minor league system, reporting to Billy Evans, then succeeded Evans as Director of Minor League Operations late in the 1940 season.[1][37]

In December 1943, R. R. M. Carpenter Jr., the new owner of the Philadelphia Phillies, hired Pennock as his general manager,[38] after receiving a recommendation from Mack. Carpenter gave Pennock a lifetime contract. Pennock filled Carpenter's duties when the team's owner was drafted into service during World War II in 1944. As general manager, Pennock changed the team's name to the "Blue Jays"—a temporary measure abandoned after the 1949 season—and invested $1 million ($17,308,129 in current dollar terms) into players who would become known as the "Whiz Kids", who won the National League pennant in 1950, including Curt Simmons and Willie Jones.[1] He also created a "Grandstand Managers Club", the first in baseball history, allowing fans to give feedback to the team,[39] and advocated for the repeal of the Bonus Rule.[40]

Pennock opposed racial integration in baseball.[1] In 1947, when Jackie Robinson was signed to the Brooklyn Dodgers, Pennock called Dodgers team president Branch Rickey before the Dodgers' series in Philadelphia and told him not to "bring that nigger here with the rest of the team."[41] He further threatened to boycott a 1947 game between the Phillies and Dodgers if Robinson played.[42][43]

Accusations of Pennock's alleged racism have come into question upon the 2016 release of the book Herb Pennock: Baseball's Faultless Pitcher written by Keith Craig. The only source of the story about the call to Rickey was from the 1976 book The Lords of Baseball by Harold Parrott who claimed to have listened in on the conversation on an extension line, something which didn't exist at the time.[44] Robinson had stated that the call was made by Carpenter and not Pennock.[45] Additionally in his book, Craig mentioned that Pennock and his wife took in a black woman who had fled an abusive husband in the 1930s, lived with their family for the rest of her life and was buried next to him.[44]

In 1948, at the age of 53, one week and four days before his 54th birthday, Pennock collapsed in the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel as a result of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was pronounced dead upon his arrival at Midtown Hospital.[46] Pennock had appeared to be in good health, even inviting friends to join him at Madison Square Garden to attend a boxing match, prior to being stricken.[47]

Honors

[edit]Pennock was honored with "Herb Pennock Day" on April 30, 1944, in Kennett Square.[1] Weeks after his death in 1948, Pennock was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.[48] In 1998, an attempt to erect a statue in Kennett Square in his honor was blocked due to his support of segregation in baseball.[42][43]

Fred Heimach, a teammate of Pennock, once called him the smartest ball player he knew.[49] In 1981, Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig included Pennock in their book The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time. He was inducted in the International League Hall of Fame in 1948.[10] Noted baseball photographer Charles M. Conlon considered Pennock one of his favorite subjects to photograph.[50]

Personal life

[edit]Pennock was nicknamed "the Squire of Kennett Square."[4][51] He married Esther M. Freck, his high school sweetheart and the younger sister of a childhood friend, on October 28, 1915. Esther often attended spring training and traveled with her husband's team during the season. Together, the couple had a daughter, Jane (born 1920), and a son, Joe (born 1925). Jane later married Eddie Collins Jr.[52] While a member of the Yankees, Pennock rented an apartment on Grand Concourse in The Bronx, where his wife and children stayed while the Yankees played their home games.[1]

Pennock was a proficient horse rider.[53] He also raised hounds and silver foxes for their pelts.[51][54] He also grew flowers and vegetables on his farm.[4]

Pennock was a Freemason and a member of Kennett Lodge No. 475, F.&A.M., in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania.

See also

[edit]- List of members of the Baseball Hall of Fame

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- New York Yankees award winners and league leaders

- Oakland Athletics award winners and league leaders

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Vaccaro, Frank. "Herb Pennock". The Baseball Biography Project. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ Grayson, Harry (June 28, 1943). "Pennock Greatest in Huggins' Book—Big Winner for Yanks". The Evening Independent. p. 12. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Farrell, Red (March 13, 1930). "Oh Yeah!". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 35. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Pennock, Phillies' General Manager, Dies of Hemorrhage: Former Major League Star Collapses In Lobby of N. Y. Hotel". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. January 30, 1948. p. 17. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- ^ "1912 American League Awards, All-Stars, & More Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ 1914 Reach Guide. 1883. p. 45. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ Macht, Norman L. (2012). Connie Mack: The Turbulent and Triumphant Years, 1915–1931. University of Nebraska Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780803240353.

- ^ a b "Selling Herb Pennock Mack's 'Big mistake': A's Pilot Observes Eighty-First Birthday by Recalling 'Boner'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. December 24, 1943. p. 13. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Herb Pennock Released". The Gazette Times. August 13, 1915. p. 10. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "International League Hall of Fame: Class of 1948–50" (PDF). MiLB.com. July 22, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "1915 World Series – Boston Red Sox over Philadelphia Phillies (4–1)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "1916 World Series – Boston Red Sox over Brooklyn Robins (4–1)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "Baseball Stars in Navy. – Many Strong Teams to Represent Sailors of Nation". The New York Times. March 22, 1918. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "1922 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ Walsh, Davis J. (December 27, 1922). "Yankees Seek Herb Pennock: Frazee Turns Down Offer Which Would Send McMillan and Cash to Boston for Pitcher". The Pittsburgh Press. International News Service. p. 22. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Yankees Get Pennock From Boston Red Sox". The Southeast Missourian. February 1, 1923. p. 2. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "1923 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "1923 World Series – New York Yankees over New York Giants (4–2)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ Evans, Billy (November 2, 1923). "Southpaw Herb Pennock Saved World Series For Yankees By Marvelous Brand of Pitching". The Providence News. p. 29. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "1924 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "1925 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "1926 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "1926 World Series – St. Louis Cardinals over New York Yankees (4–3)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Babe Has Praise For Herb Pennock: Yanks' Southpaw Pitches Wonderful Game Against Pirates". The Telegraph-Herald and Times-Journal. Dubuque, Iowa. October 9, 1927. p. 19. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "1927 World Series – New York Yankees over Pittsburgh Pirates (4–0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "1928 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "1928 World Series – New York Yankees over St. Louis Cardinals (4–0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Herb Pennock Has Neuritis Again". The Pittsburgh Press. May 3, 1930. p. 11. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "1930 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "1931 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "1932 World Series – New York Yankees over Chicago Cubs (4–0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ a b "Pennock Released By New York Yanks". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. January 6, 1934. Retrieved September 12, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Boston Gets Herb Pennock". St. Joseph Gazette. Associated Press. January 21, 1934. p. 9A. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Herb Pennock Up With Best: Yankee Pitching Ace Tied Jack Coombs' Record in Recent Series". Providence News. October 13, 1927. p. 10. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Herb Pennock To Manage Charlotte". Rochester Evening Journal. Associated Press. January 2, 1935. p. 18. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Herb Pennock to Remain With the Red Sox Doing Duty as First Base Coach, Declares Cronin". Daily Boston Globe. March 4, 1936. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ "Evans Succeeded By Herb Pennock". The Christian Science Monitor. October 9, 1940. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ "Herb Pennock Takes Philly Position". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. November 30, 1943. p. 35. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "Grandstand Manager's Club Formed by Phils". The Hartford Courant. September 2013. p. 19. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Herb Pennock Raps Major League Bonus Rule. Phillies Head to Urge Law Repeal: Present Rule Called Drawback to Clubs, Players; Simmons May Be Test Case". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. October 28, 1947. p. 11. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Manasso, John (July 8, 1998). "Racial Issues Tarnish Hall Of Famer Tribute Chesco's Herb Pennock Was A Hero To Many, But Some Say He Didn't Always Act Like One". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "Herb Pennock: Racial stand snags statue plan". Star-News. July 18, 1998. p. 2A. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Fulwood III, Sam (August 14, 1998). "Heroes of Yore May Not Be Evermore: Pennsylvania town's attempt to honor Ruth-era pitcher Herb Pennock draws fire over alleged racist remarks. Issue raises questions about standards used in judging others". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Barber, Chris (July 11, 2016). "New book asserts Pennock was no racist". Daily Local News. Exton, Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 11, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Frank (November 7, 2014). "Racism claim still clouds Hall of Famer Pennock's reputation". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "Herb Pennock Dies Suddenly: Phils' Official Collapses in Hotel". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. January 30, 1948. p. 26. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "Herb Pennock Dies: He Erased Futile From The Phillies". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. January 31, 1948. p. 6. Retrieved September 14, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hand, Jack (February 27, 1948). "Pitcher Herb Pennock, Buc's Pie Traynor Elected to Cooperstown Hall of Fame: Al Simmons Is Third in Writers' Vote". Deseret News. Associated Press. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ Butler, Gul (September 21, 1943). "Herb Pennock Smartest Twirler". The Miami News. p. 2–B. Retrieved September 12, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Williams, Joe (April 3, 1930). "Herb Pennock Photographs In Graceful Fashion". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 33. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Carey, Art (March 28, 2008). "Baseball's other Hall of Fame At Burton's Barber Shop in Kennett Square, local stars are immortalized". philly.com. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Collins' Son Will Marry Daughter of Herb Pennock". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. October 25, 1941. p. 2. Retrieved October 6, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Herb Pennock Is Some Jockey, As Well As A Real Pitcher". Boston Daily Globe. February 24, 1923. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ Pegler, Westbrook (September 26, 1932). "Pennock Is a Foxy Fellow; He Raises Fancy Fox Furs". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 21. Retrieved September 12, 2013. (subscription required)

External links

[edit]- Herb Pennock at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- The Deadball Era

- Herb Pennock at Find a Grave

- 1894 births

- 1948 deaths

- American Quakers

- Baseball executives

- Boston Red Sox coaches

- Boston Red Sox executives

- Boston Red Sox players

- Buffalo Bisons (minor league) players

- Major League Baseball farm directors

- Major League Baseball general managers

- Major League Baseball pitchers

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- New York Yankees players

- People from Kennett Square, Pennsylvania

- Baseball players from Chester County, Pennsylvania

- Philadelphia Athletics players

- 20th-century American sportsmen

- Philadelphia Phillies executives

- Providence Grays (minor league) players

- United States Navy personnel of World War I

- Westtown School alumni